In my research, I often collaborate with non-academic actors to generate new knowledge about how we can manage and care for landscapes more sustainably. Those actors can be people working with spatial planning or nature protection in municipalities, farmers, entrepreneurs in nature tourism, or representatives from outdoor recreation organizations. In my research, I invite this diversity of actors to come together and meet in workshops, to discuss challenges and do exercises together where the different insights, experiences and various forms of knowledge that the actors have about the landscape can be combined and built upon. This process of weaving the knowledges of different actors into something new is called knowledge co-production.

This is what I did for my PhD research. I collaborated with the staff at the Kristianstad Vattenrike UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, but also invited various other actors who care for the landscape in the Helge å catchment area in southern Sweden.

At a conference in 2019, I met Ida Wallin. It turns out, she had also done her PhD in the Helge å catchment using knowledge co-production. Not only that, she knew of two other projects with a similar landscape management focus from the same study area. After a winding and wornderful three year journey, consisting of many long conversations over Zoom in our respective COVID-19 isolations, we ended up producing a paper together comparing these four projects. In October 2022, it was published in the scientific journal Ecosystems and People, with the title:

Knowledge co-production in the Helge å catchment: a comparative analysis

It is generally acknowledged in the scientific literature that to be successful, knowledge co-production must be adapted to local contexts. This makes comparisons between different cases of knowledge co-production challenging, as conditions can vary greatly. That Ida and I had identified four projects from the same study area, involving similar local actors, all focusing on landscape management was therefore a unique opportunity to compare cases from the same context and hopefully glean some more general patterns in what makes knowledge co-production work.

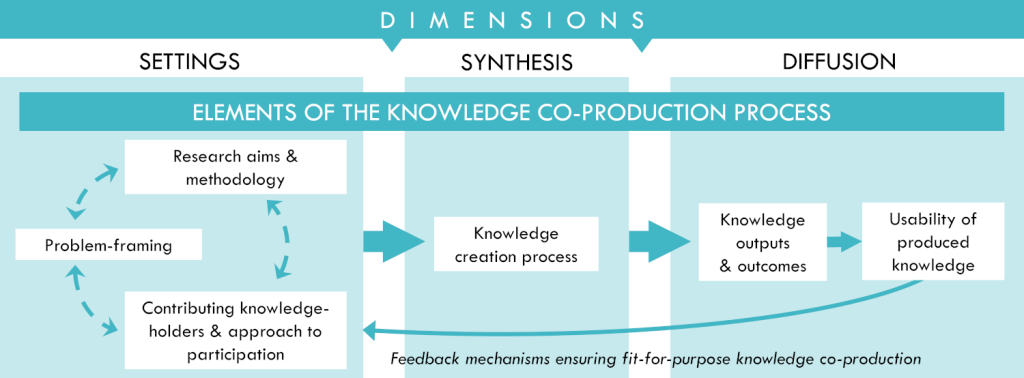

Based in existing scientific literature, we developed an analytical framework to represent the knowledge co-production process. This helped us to systematically compare different facets of the processes in the four projects.

To inform the comparison, we gathered information from the different research teams, from their published papers and project reports, as well as discussed initial findings with them in an online workshop. We also interviewed key non-academic participants from all four projects about what they thought about the knowledge co-production processes.

What we learned

Through this systematic comparison, several insights emerged:

- Framing a project together with local actors and having a flexible process design that can address new local issues when they emerge improves chances of the co-produced knowledge being seen as usable by the actors who participate.

- It is beneficial to continuously engage in reflexive practices among researchers, for example discussing methodological and ethical challenges that emerge in interactions with the participants. Such reflexive practices can hone the researchers co-productive agility and capacity to make situational judgements, allowing them to adjust the process as it unfolds.

- Trade-offs may occur between addressing local concerns and contributing to international comparisons, for example in large research consortia that a project might belong to. Both focusing on the local and contributing to international comparisons are valid motivations for a research project, but transparency about research goals or what is being emphasized in the project is crucial to set the right expectations among the participants.

- Finally, we encourage researchers who want to engage in knowledge co-production to think longer than single projects. Forming long-term relationships between practitioners and researchers, as well as between different research teams, will improve the quality of both the research and the usability of the knowledge that is generated. Over time, these relationships may also inspire new directions for practice and research alike.

REFERENCE

Malmborg, Katja, Ida Wallin, Vilis Brukas, Thao Do, Isak Lodin, Tina-Simone Neset, Albert V. Norström, Neil Powell and Karin Tonderski. 2022. Ecosystems and People 18 (1): 565-582. https://doi.org/10.1080/26395916.2022.2125583