Life, with the garden

Location: Oaxaca, Mexico • • • Visit: November 2017

In the end of October 2017, I went to Mexico for a conference. The trip there was eventful. I landed in Oaxaca completely shaken up by delays and jet-lags and being lost on strange, dark 3 AM streets. On top of a general exhaustion from being a PhD student. It wasn’t the best of circumstances. Especially to enter straight into the Día de los Muertos celebrations in Oaxaca.

There are individuals on the internet who claim that Oaxaca is the place to be for Día de los Muertos. I have no way of corroborating this claim, since I’ve only ever been to Oaxaca, but this I can say: They seem to have spared no expenses for this celebration. There was a carnival-like atmosphere in the old city center, with live concerts, dance performances, exhibitions. People everywhere with faces painted like skulls. Flowers and piñatas hanging from windows, and mezcal, mezcal everywhere!

And it was exciting, yes. But also, while I was standing there in the square by the Santo Domingo temple, I got this uneasy feeling in my chest, like someone was squeezing me a little bit too tight. Two papier-mâché giants were dancing to the tunes of a small brass orchestra, with the late afternoon sun making all the costume-clad children look like fairy-tale silhouettes. But. Although the dancers and musicians and children amounted to a fair number of people, I think the amount of people around, watching, with cameras and I’m-not-from-here written all over their outfits, were twice as many. This was a spectacle, and it made me want to just get out of there.

It isn’t that I disapprove of the celebration as such. Not at all. I find this way of celebrating the memory of the dead nice, actually. I do not believe in forgetting and I also do not see death as something to be afraid of. We should acknowledge death, and the memories of the people we have loved, but lost. I was brought up with a similar tradition, the Swedish All Saint’s Eve, when we always went to light candles on the grave of my great grandmother, and later grandparents. The Mexican altars that people set up in their homes, with flowers, photos, and the favorite foods and drinks of the dead, is a similar way of honoring the memories. As is the lively picnics that people have next to the graves of their dead loved ones.

What I think upset me about these first days in Oaxaca, was how this profound, deeply emotional celebration had been hijacked by flocks of backpackers looking for an exotic and exciting party. It made me feel dirty, somehow. Like I was part of soiling something sacred. Tour companies sold package deals where you could combine mezcal tastings with tours of the cemeteries at night, where people would party until dawn. The thought of it made me feel queasy.

Now, I know that tourism is a very important income for many people in Oaxaca. During the days of the Día de los Muertos celebrations, every single hotel, hostel and AirBnB is fully booked. Restaurants are bursting with people. Hosting this festival provides a huge source of income for the city of Oaxaca. And all the local people I spoke to only expressed excitement and approval of outsiders coming and experiencing their local traditions (all these people made a living from the tourists, however, so I do not know how representative they are of Oaxacans in general).

And maybe my feeling of “dirtying” of something is a misplaced value judgment of what is “genuine”, a sentiment if acted on forcing “the other” to “conserve” their exotic traditions for the benefit of my experience. Like what is sometimes said about “conserving” policies towards indigenous groups in western countries, where their traditions are romanticized and not allowed to evolve according to the needs and preferences of the groups themselves. I don’t know. Of course, people have a right to make a living. And of course, people have a right to experience exciting, exotic things. I myself am a big believer in traveling as a way to become a more understanding, conscious world citizen. And if lots of people find the same things exciting, well, then you will get a lot of tourists attracted to the same places. No helping that.

This combination, though. Flocks of tourists and the sacredness of honoring the dead. To me, it just felt wrong. Not in a universal sense, I do not claim to have the right to judge anyone in this. I do not even fully understand where my own feelings regarding this come from. What should have been an exciting experience, just made me incredibly uneasy.

Or maybe it was just the exhaustion from arriving in Oaxaca. The last night of the celebrations, I painted half of my face. A small challenge of my own feelings. It felt OK.

After the celebrations of death had ebbed out, Oaxaca returned to what I think is its normal pace: A couple of bustling streets and busy markets, and otherwise, calm, leisurely, with few people seeming in a rush to get anywhere. And I liked it so much better.

After a couple of nights proper sleep, and days of few musts, I was ready to take it all in. The colorful, elaborately decorated buildings. The massive stone walls and gilded inside of the church of Santo Domingo. The street art and sundrenched mountain views.

Or just having hot chocolate and bread in the bustling Mercado 20 de Noviembre market. Oaxaca is a friendly city, amazing to wander around in, or just sit and enjoy. I really liked it.

The Oaxaca attraction I looked forward to the most was the ethnobotanical garden. Ethnobotany has become one of my academic side interests, ever since interviewing farmers about practices and plants in Burkina Faso while walking through the village savannah landscapes.

Upon arrival, however, I realized the only way to enter was to take a guided tour. In Spanish, because none of the three English tours a week fit with my conference schedule. No planlessly wandering around, no solitary exploring. Such a disappointment. Well. I went for the Spanish one-hour tour, and by the end of it, my disappointment had waned. Apparently, they used to allow visitors to wander around freely in the garden, but had so many plants stolen that they had to restrict the visits to guided tours (or so I understood the guide – my Spanish is far from fluent).

And to be fair, there is a point to having a guide explain the garden. There were no signs, but the guide was incredibly knowledgeable and explained all about the wild and the cultivated, the native and the species that were brought here by the Europeans. The state of Oaxaca, according to the guide, is an incredibly biodiverse place and is home to more plant species than grows wild in all of Europe. And the different peoples of Oaxaca have been using the plants for everything from food and medicines to fiber production and dyes for centuries, way before the Spanish arrived with their monks to catalogue it all.

The garden was organized into the different vegetation zones that exist in the state of Oaxaca, from the high-altitude drylands to the lowland lush forests, and it is just as much a place for research as a plant museum. In 2017, for example, they had just finished a climate-controlled greenhouse where plant experiments will be conducted, testing how different species will react to changing climates.

The garden lies in the former monastery, the beds separated by a grid of narrow gravel paths and surrounded by the high monastery stone walls. It was originally part of the 17th century monastery grounds, and it wasn’t opened as an ethnobotanic garden until 1998. The surrounding buildings, the former Santo Domingo monastery, now houses the Museum of Cultures of Oaxaca. The museum systematically displays its extensive collection of artefacts and through its windows one can see the dense greenery in the ethnobotanic garden and, beyond the city, all the way to the mountain tops in the horizon. The garden and the museum together offer an intense crash course in the fascinating social-ecological history of Oaxaca.

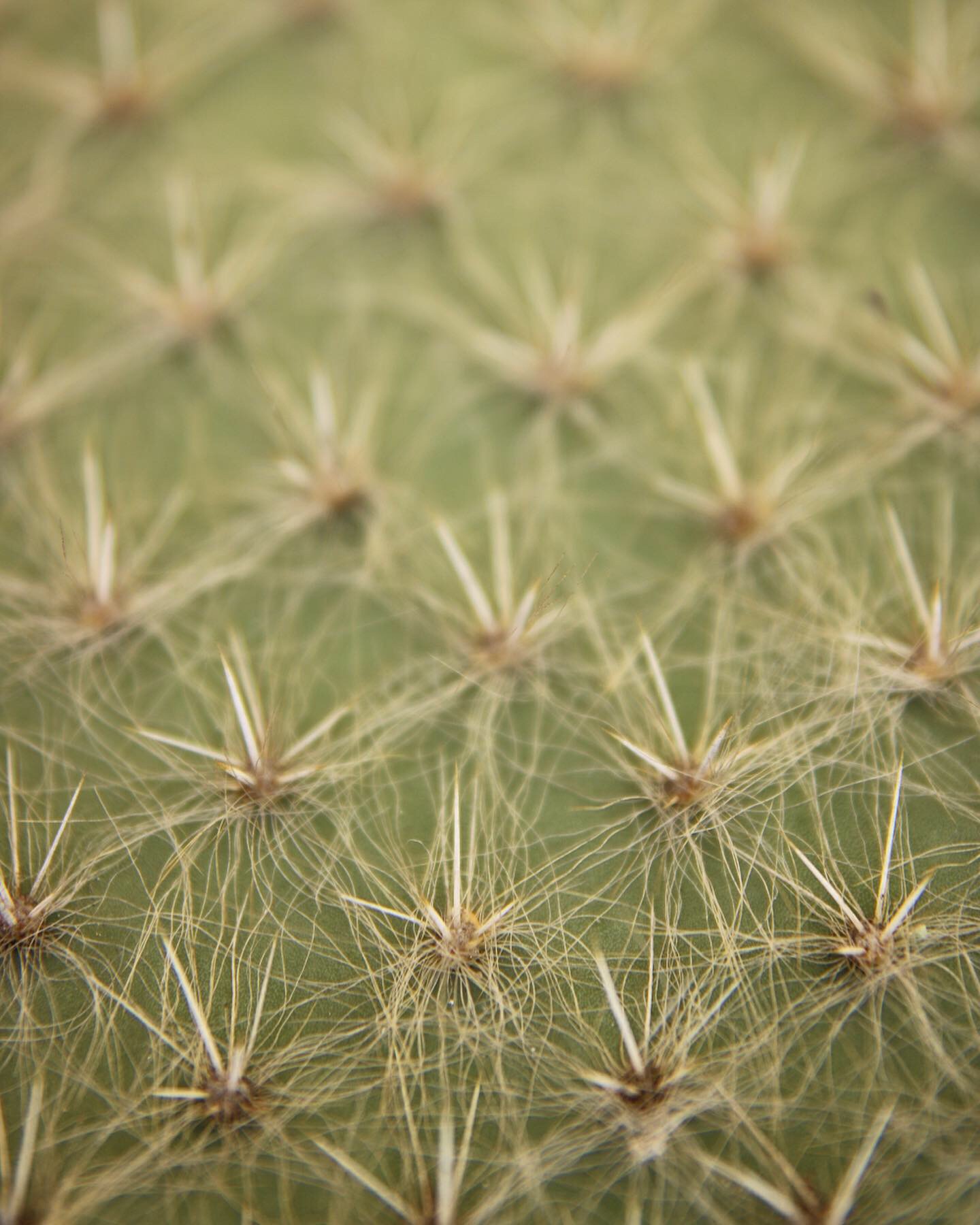

The garden was small, but dense, and there was much to learn. It is worth visiting. I think I liked the variety of cacti the most: The life force in these inhospitable plants, and the beauty in the patterns on their skins. It amazes me. This is pure survival. And I must admit, the cacti and pond installation in the end of the tour were a masterpiece of organic symmetry and reflection. I would have liked it better, though, if I’d been allowed to wander around on my own after the tour, to marvel at garden design and the cacti in a little bit more intimate and slow detail.

I found a favorite café in Oaxaca. A chocolate place, only big enough to fit three small tables and the counter, squeezed into the one-story building opposite the Santo Domingo church and walls of the ethnobotanical garden. The floors had earth-red tiles and the cold cardamom chocolate that they served was divine. I don’t know how many I had over the course of my stay in Oaxaca.

The coolness of the small space, and the open doors giving a view of the calm street and massive, sundrenched walls of the church, made it a perfect place to sit and think. Read. Make notes. I had ideas. Felt a kind of excitement about writing stories that I haven’t felt for years – I’ve been too busy writing science to think about stories. But there was something about the old buildings in this colorful town, walking around in sandals in a strange place, creating new, temporary routines. It triggered me. It always has. I never write as much as when I’m on the road. For the last decade, though, that has mostly meant blogging. Here, the fictions in me started stirring from their decade-long slumber. Maybe, I can start writing fiction again.

I felt filled up. But also, there was a note of melancholy behind the joy. This elatedness and inspiration that I feel when wandering around in a strange place, it has become so rare. I don’t travel as much as I used to. I don’t want to fly. The joy I get from writing can’t depend on me going far far away to get inspired. I need to develop my ability to get the same kind of inspiration closer to home. In people, maybe. Or art. Music. Challenging my senses in my own backyard. A new mission.

At the chocolate place in Oaxaca, though, this was just a fleeting thought. I was enjoying myself too much in my new-found state of inspiration.

The conference, organized by the Programme on Ecosystem Change and Society, was intense, inspiring, exhausting, and I learned so much. Too much, maybe. By the end, my brain was overflowing with impressions and ideas, and it completely overwhelmed me, thinking about what to do with it all. I would need time to land in it.

The conference ended with an extravagant party, with food and mezcal and performances. And it was like everyone was floating on the wave of a successful, inspiring conference – and now, the wave broke. An extreme discharge of energy. Everyone dancing, from master students to world-renowned professors. And I will forever remember this: Dancing salsa barefoot on the grass under the starlit sky. A perfect moment in time.

The next morning, after only a couple of hours of sleep, My, Ashley and I got picked up for a last fieldtrip. Up to Mixteca alta, to see monasteries, geological formations, temples and learn about Mixtec mythology, handicraft and food traditions from members of Mixtec mountain communities themselves. Beautiful, interesting, incredibly educational – but through it all, I felt like walking through a haze. Sleep-deprived, over-exposed and more than saturated with inspiration. I simply couldn’t take it all in.

At dusk on the second day, when we had started the journey back to the city along the winding mountain roads, I’d had enough of conversation. I put on my headphones and turned to the green slopes outside my window.

And without really thinking about it, I put on a mix of First Aid Kit songs. While Johanna and Klara were singing about bitter winds in Stockholm and how they’d rather be broken than empty, I watched clouds roll over the mountain ridges like dough rising over the edges of a bowl, and I remembered: I’ve felt this before. Not once, but twice. The harmonized voices of Johanna and Klara, a journey, meetings that touched something deep, and watching high mountains pass outside a bus window. The first time, between Sarajevo and Belgrade in 2013. The second time, between Å and Narvik, northern Norway, 2014. And now, somewhere in Mixteca Alta, Mexico, 2017.

Mountainous transit linkages across time.

Eight months later, August 2018, remembering Oaxaca:

It’s been more than half a year, now, but at the hostel in Oaxaca, in the mornings before the adventurous twenty-something backpackers had woken up yet, I read. In the tiny inner courtyard, with the small mossy fountain and potted plants, there were hammocks and the black cats would walk by, stroke their sides against my back, wanting to get scratched for a minute, and then jump up on the not-yet-opened hostel reception counter to watch over the waking guests. It was calm, in the fragile light of the morning sun.

The book I was reading was a history of female mental illness in the early twentieth century. The title of the book was ”Den sårade divan” (“the wounded diva”) and it was written by the Swedish historian Karin Johannisson. It was a fascinating read. The main argument in the book revolves around the narrow and inflexible role of the middle- and upper-class woman in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The expectations on her. Beautiful, pleasing young woman, wife, mother, keeper of a household. How this, if a woman could not fit into that form, sometimes took the shape of mental illness. Women being admitted to mental institutions for weak nerves, hysteria, schizophrenia, paranoia. Immoral behavior.

Particularly with female artists at the time, being admitted was not uncommon. During the Romantic era and afterwards, the artistic genius was celebrated as something higher, nobler. That is, the male artistic genius. The same erratic, eccentric, rule-breaking behavior in a woman was considered sick, against nature, and had to be cured or locked away. And Johannisson tells this story of repression through the lives of the author Agnes von Krusenstjerna, painter Sigrid Hjertén and poet Nelly Sachs.

I had a brief obsession with Agnes von Krusenstjerna when I was seventeen. I read all the books in her series about the misses von Pahlen, which starts out as a beautifully written, but still quite banal story of a broken-hearted lady in a manor taking in the orphaned daughter of her brother. However, during the course of the seven books, spanning the two first decades of the twentieth century, the story develops into something quite exceptional. The type of liberal and alternative family relations described in the end could be considered controversial even today. So imagine how they were received when the books were published back in the nineteen-thirties. At seventeen, I read them as a feminist manifesto, and loved them.

I read a collection of Nelly Sach’s poems in 2010. She was Jewish and born in Germany in 1891, and managed to flee to Sweden with her mother during the second world war. She was awarded the Nobel prize in literature in 1966, and was accompanied to the award ceremony by her psychiatrist. In my notes from 2010, I wrote: ”the pain [the poems] expressed, that was heavy. [some] I didn’t get at all, but [others] had a sort of abstraction, emotion, I don’t know, appeal that moved me.” So, a mixed bag, I guess.

And just the other week, I went to an exhibition at a gallery in Stockholm, showing paintings by Sigrid Hjertén. The colors so vivid, constant, expressing emotions, shapes moving from clarity to abstraction throughout her life, ending up in something almost completely disintegrated before she died of a failed lobotomy. And the heart-breaking isolation – or is it just that I see it, because of what I know about her life?

Because what these three women had in common, in addition to being part of the absolute avant-garde of the Swedish art scene of their time, is that they spent considerable amounts of their time in different mental institutions. Voluntarily, or admitted by their families. But what Johannisson argues, by having studied their medical journals, is that they were not only victims of a patriarchal society that considered them improper, misfits. To a certain extent, there is an agency in their illnesses. They are unstable and self-destructive, yes, but also at times very deliberate in their acting out of the disease. At the institutions, they are allowed to behave as eccentrically and erratically as they please – because they are not women, they are crazy. Normal societal expectations do not apply.

In this way, there seems to be a sort of dialogue between the female artist and the societal expectations on the woman. The creative personality of the artist is considered abnormal in a woman, forcing her into psychiatric diagnoses – but in that process, the female artist can use the temporary boundlessness that the diagnosis allows her to act out her creativity. Safe within the uniform of the insane. All three of the chronicled women create some of their most inspiring art either while hospitalized, or during periods between being admitted.

This is not to belittle the very serious issue of mental illness. Johannisson never claims that either of the three artists were not struggling. Like many people with creative dispositions, they were probably very sensitive, prone to depression, manic episodes, paranoia. But the fact that they were not allowed to deal with this through creating art as freely as their fellow male artists probably exacerbated their issues. And the varying degrees of freedom from judgement that they felt at the mental institutions must have felt like a relief, mixed up with the anguish and darkness they were already struggling with. Their medical journals suggest that they at times acted out the role of whatever diagnosis had been assigned to them, because it granted them more freedom than being a woman in the world.

That trip to Mexico was tumultuous in many ways. That can be part of the reason why Johannisson’s book made such a strong impression on me. The right book at the right time. Things have changed since the early twentieth century. Women are not admitted to mental institutions for hysteria. In many ways, gender roles have become much more flexible and porous. But in other ways, also not. For both women and men, societal expectations are creating a lot of unease and distress. It still requires courage, confidence and a touch of recklessness to act outside the norm, and people’s reactions to your norm-breaking behavior still varies depending on who you are.

But reading this book encouraged me. Made me feel like it is okay that people sometimes call me weird and crazy. It became like a protective blanket there in Oaxaca, at the conference full of intelligent, interesting people, the vulnerability I always feel when trying to make a connection. The erratic behavior of my inspiration. It made me realize I need to forgive myself my unease. And that sometimes, maybe leaning into it instead of hiding it will make me feel more at home in my own body. Make me freer.

I still carry that feeling with me. Like a talisman. And I am going to put up a Hjertén reproduction on my wall. To remind me, for whenever I am feeling lost.