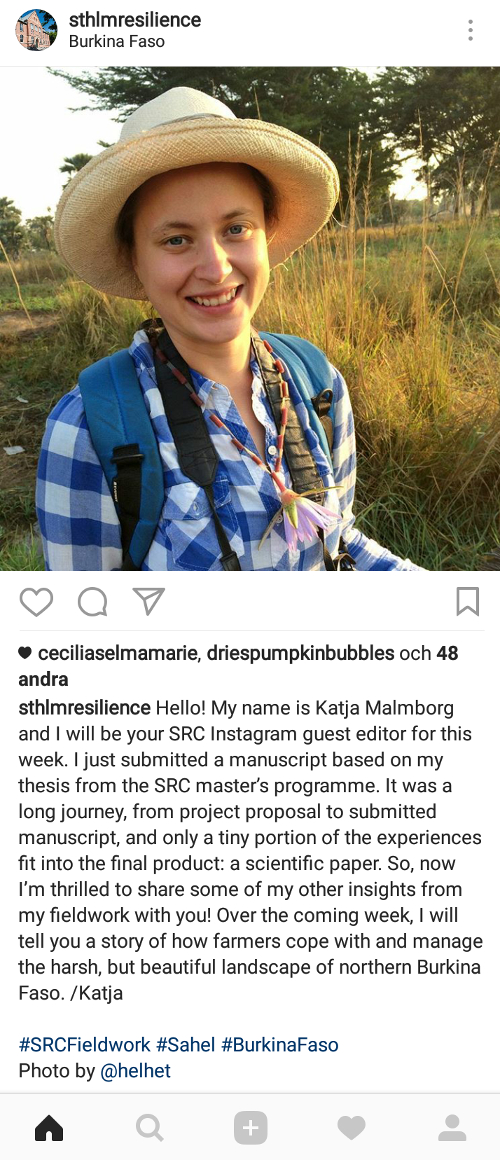

Some weeks ago, I was the guest editor of Stockholm Resilience Centre’s Instagram account under the hashtag #SRCFieldwork. Every week, a master’s or PhD student or researcher at the center posts photos and tells stories from their fieldwork experiences. The idea is to give some insight into the work behind the research and also share some of the stories that would never make it into a scientific publication but that can be just as important for understanding a system, situation or problem. And, of course, everyone has to be on social media now – even us dry researchers. We’re increasingly being encouraged to get our messages out there through these new channels of communication.

Social media is in no way new to me as such. I got my first pre-Facebook, pre-blog-boom online community account when I was twelve, and have been writing things online ever since. A lot of my writing has been about traveling and about books. I’ve written about my fieldwork in a similar, travel journal kind of fashion. This Instagram-editorship, however, was the first time that I’ve seriously tried to synthesize my scientific knowledge and research experiences in a concise and systematic way. My week of being the SRC Instagram guest editor writing about my master’s thesis fieldwork experiences gave me a first real taste of what it could be like to wear the hat of researcher on social media – and I must admit I liked it! I ended up spending quite a lot of time picking topics, choosing photos, structuring the story. I didn’t quite want to let it go after my week was over, so I decided to put my posts up here too. Enjoy!

Day 1, #1

Day 1, #2

In northern Burkina Faso, approximately 90 percent of the population lives in rural areas and has agriculture as their main livelihood strategy. This region is semi-arid and rainfall is highly variable between years, leading to people having had to adjust their farming practices to the extreme climate conditions. In many rural communities, traditional agroforestry methods are still used. Small fields of sorghum, millet, maize and legumes are combined with trees, shrubs and fallows, creating a patchy, multifunctional landscape of both domesticated and wild plants.

Day 2, #3

The main goal of my fieldwork was to visit 13 villages to collect groundtruthing data for a land use classification of satellite imagery that I was going to make later. The idea was simple: I would walk in a straight line from the village center, stopping every 100 meters to register GPS coordinates and take photos. Well, it was not simple. With me, I had two farmers from the village to answer questions about management practices, etc. Conducting interviews while walking straight, no matter what came in my way, dense shrubland or rocky hill, in almost 40 °C heat. One day of groundtruthing meant 10 km of walking in total. This was nothing for the farmers, of course, but I have a feeling they found my panting and red, sweaty face curiously amusing. I regularly drank five liters of water a day. Still, I managed to stop occasionally to admire the amazing landscape I was walking through.

Day 2, #4

Livestock is an integrated part of smallholder farming practices in the Sudano-Sahelian zone of Burkina Faso. Cattle, sheep, goats, donkeys and fowl roam the land and eat whatever is left once the fields have been harvested. Often it’s the children who herd them, and the manure is an important source of fertilizer for the fields. The small ruminants are sometimes slaughtered for festive occasions, but mainly they are kept as insurance. If the harvest fails, or if the family needs to invest in something, they can sell an animal and get the cash they need. Cattle are also seen as a sign of status and influence, and bulls and donkeys are trained to plow the fields.

Day 2, #5

This is Hamado, the chair of the farmer’s association in his village. In the pink evening haze, he and his donkey are bringing home the haulms of the groundnut harvest. The nuts have already been picked from the roots and will be shelled before storage or transport to the market. The stalks will also be stored and given to the animals as fodder during the dry season.

Hamado says: “It is important that we have fodder for our animals. I tell the farmers in my village to not turn all their land into fields, but to also keep some as shrubland. The shrubs and herbs are an important source of food for the animals, but also provide wild fruits and seeds that the women harvest and medicinal plants that we use if someone gets sick.”

Day 3, #6

In the multifunctional landscape of northern Burkina Faso, the smallholder farmers don’t only cultivate their crops and herd their animals. Certain wild trees, shrubs and herbs are actively being managed as integrated parts of the agricultural landscape and harvested for their uses as food, fodder, medicines and for religious ceremonies, and are important sources of nutrition for both humans and animals.

This is a baobab tree (Latin: Adansonia digitate). It has a sweet and nutritious fruit that ripens just before the rainy season starts and that kids love to pick. The leaves are dried and used as condiment in soups, and can be used to treat asthma. Both fruits and leaves are also sold at the market, giving the villagers a small but important source of cash income.

Day 3, #7

Noon is not a fun time to be out and about in northern Burkina Faso. The sun is excruciating and the heat like a vise pressing at your temples. Luckily, the farmers have prepared for this, constructing combined shelters/fodder storages and planted mango and neem trees to provide shadow. When the day is at its hottest, everyone takes a break from work, sitting down in the shadow to eat lunch and socialize. I was often asked to join in their meal. Here, we ate tô, the staple porridge made out of sorghum. You take it with your hand and dip in a sauce made with a wild type of spinach. A little bitter, but very filling.

Day 3, #8

Fieldwork in a place like rural Burkina Faso sometimes requires a little bit of ingenuity. As my fieldwork partner, I had Elli (@helhet). She was in Burkina to collect soil samples and measure water infiltration and evaporation. However, some tools turned out to be hard to find. No matter – Elli decided she could do it herself. She bought ordinary plastic pipes and rusty tools at the market and spent a couple of evenings in our room swearing over the dull saw. But she prevailed, and managed to construct her own rudimentary lysimeters! Over a period of two weeks, she then weighed these soil-filled pipes at dawn and dusk, as a way to measure the rate at which water evaporated from the soil in different locations in the village. This is an important indicator for how good the soil is to farm in, especially in a dry place like northern Burkina Faso.

Day 4, #9

The wild shrubs and trees in the multifunctional landscape of northern Burkina Faso are also used as a source of firewood and building material. It is often gathered by the women from the outskirts of the village. Everyone has a task to fill, from the children herding sheep in the afternoon after school, to the old man sitting under a mango tree carving pickax handles.

Day 4, #10

Soil degradation is a serious issue for smallholder farmers in northern Burkina Faso. They use many strategies to deal with this. One of them is the Zaï (pictured), a soil and water conserving technique in which manure and other organic matter is dug into pits in the poor soil. This increases soil fertility and water infiltration, and sometimes makes it possible for herbs and shrubs to sprout there. These wild plants, in turn, loosen up the highly compacted soil with their roots, which makes it possible for the farmers to plant crops on these lands again.

Day 4, #11

Written in my field notebook: “During the afternoon transect walk in a village called Tarba, we ran into a big herd of cattle. The afternoon walks are the best. When the heat has started to subside and the light has turned soft orange. The smells come out then too: the dry earth, the harvested fields, the mint-and-thyme-smelling weeds. The cows stirred up dust, making the air shimmer in the light of the setting sun. After a long hot day, the temperature was just perfect, and there was a light breeze. One of the boys who was herding was walking with a little puppy by his side. He was singing, in a clear boy’s tenor, and the puppy was happily running back and forth between the boy and the cows. As if playing at being a shepherd dog.

One of those beautiful moments, walking through the fields and shrubby fallows together with a singing herder boy, his puppy and his cows, while the sun set in a shimmering golden mist.”

Day 5, #12

One way for smallholder farmers to build resilience in the highly variable climate in semi-arid Burkina Faso is to harvest rainwater. Dugouts and small reservoirs, like here, are mostly used for watering animals, while larger reservoirs can be used for aquaculture and irrigation of rice, maize and vegetables. Access to irrigation water can be an important source of both income and nutrition during the dry season, but is problematic. Dams are costly to keep up, the landscape here often leads to high sedimentation rates into the reservoir, and if not governed well and fairly, the reservoirs and the new water resources can lead to increased pressure on the land, rising inequalities in the villages and displacement of farmers.

Day 5, #13

Things rarely go as planned when in the field. In October 2014, barely halfway through our fieldwork period, the president of Burkina Faso of 27 years, Compaoré, decided to propose a change to the constitution that would allow him to be elected for yet another term. This led to big protests in the major cities in Burkina Faso. The parliament was set ablaze and other governmental buildings also. Compaoré was forced to flee the country and a transitional government was set up, followed a year later by the first democratic elections in almost three decades.

During the most intense week of the popular uprising, Elli (@helhet) and I were told to stay put in our room. For a couple of days, we did not know which way the protests would go: peaceful transition or escalating violence. The contrasts were extreme, butterflies fluttering in the quiet backyard of our guesthouse in rural northern Burkina, and the confusing messages of closed borders, burning cars and hijacked TV stations in the capital. It was nerve-wrecking. Nothing bad happened to us, though, and after less than a week we could return to our fieldwork, having witnessed the first step in the (mostly) peaceful transition towards democracy in this West African country.

Day 5, #14

To wind down in the evenings, and especially to not lose our minds during those days of being cooped-up in our room during the 2014 Burkinabe uprising, Elli (@helhet) and I watched quirky sitcoms and ate Swedish candy. I basically never eat candy at home, but in the field Gott&Blandat became like a safety blanket.

I also designed two pairs of mittens. If you want to see the result of my fieldwork de-stressing, check out Elli’s Burkinabe elephants and Vivi’s reindeer at @becausekatjasaidso. Also, if you want to learn more about my classmate Vivi’s fieldwork involving, guess what!, reindeer and craftsmanship, stay tuned. Vivi will be the SRC guest editor later this spring.

Day 6, #15

The last thing I did in each village I visited in northern Burkina Faso was to return and present the preliminary results of my interviews and groundtruthing. I did this to allow the villagers to learn what I had discovered in all 13 villages, but also to let them correct me if there was something that I had misunderstood. There were always more people at these meetings than the 4-6 farmers that I had interviewed, ranging from the village elders to heaps of children. These conversations were really inspiring and I believe we learned a lot from each other.

Day 6, #16

In Burkina Faso, they give gifts. In each village that I worked in, they gave me something: More groundnuts than I could ever eat, beans, watermelons. I even got two live hens! The generosity, both with regards to time and resources, of the people I met astounded me.

Day 7, #17

I think the best chance consequence of my choice of master’s thesis was to end up in the same field sites as Elli (@helhet). I’m not saying that anyone should choose their project based on where their friends are, but having someone to share everything with can make things so much easier. With all the twists and turns that unraveled during the course of our months in Burkina Faso, I’m not sure if I would have been able to come back with so much data and so many positive memories without the support and mere presence of Elli.

Here, we are photographed with Kassoum and Madi, who were members of the farmer’s association in the village where Elli worked and incredibly helpful in the challenging task of collecting soil samples from the dry, hard earth of northern Burkina Faso.

Day 7, #18

And then there was Abouleh. A former chair of the farmer’s association, but now just the man who knew, whom everyone turned to when there were issues with the farming. He welcomed us when we came to his village, he introduced us to everyone who mattered and he waited for us after our walks, wanting to hear if I had gotten everything I needed. He said: “I am a farmer. I care for my land, for my animals. You only ask about the farming now, but the animals are important too. Say that to your colleagues, tell them: The land and the animals and us cannot be separated.”

Day 7, #19

I’ll miss the sun rising over the shrublands. The smells of dawn, soft, dry and earthy. The sounds of donkeys and goats. The desperation in a donkey’s scream, or the very un-animal-like braying of the goats. Wherever I heard them, I couldn’t help laughing. And the people. I’ll miss working with the farmers. Their knowledge, sincerity and helpfulness, going out of their way to make sure I got what I needed. I am humbled by this landscape and the people who live there, and can safely say that my experiences from doing #SRCFieldwork changed my life.

Day 7, #20

Although fieldwork can be truly fun, it is also exhausting. You have to take the time to have some frivolous fun too. The last five days in Burkina Faso, we took the bus south and did some proper touristing in hippo lakes and waterfalls around Banfora. And so, with this photo of me standing on top of one of the Domes of Fabedougou, I conclude the story of my fieldwork in Burkina Faso. I want to thank you for this week. Barka!