The older I get, the more on edge with time I seem to become. I cannot estimate how long things might take to complete – but also, I cannot let go of the things I thought I would have time to do. I used to be better at it. I did not use to come late to everything. It is the beginning of things that excite me – no, not even that. It is the thought of beginning something that gives me that tingly feeling of being alive. So not having time to start something disappoints, and not being able to let go of that remembered excitement makes my list of things-to-do grow ever longer.

That is what happened with my 2018 pop cultural summary. Too many things that I was excited about. But here I am, now, two months into 2019. Ready to give it a try.

MUSIC

Another year of not listening that much to music. First Aid Kit came out with a new album. It was OK. I discovered that Queen is great exercise music, especially “Can’t stop me now”. As always, Säkert!’s EP “Arktiska oceanen” was wonderful. In one of the songs, Annika describes how she flies across the Atlantic together with trees, ants and polar bears to Washington, and she: “oh God I felt foolish for having thought I was more important than the ocean”. So beautifully written!

But I think, emotionally, what stuck the most during 2018, was Ane Brun’s cover of “By your side“. It is like a blanket, warm, safe, something to hide in just for a moment when the world feels too hard and tough. And it’s doubly nostalgic: My dad listened a lot to Sade, the original artist of “By your side”, when I was a kid. And Ane Brun was one of my favorite artists during my late teens, the most intense pop-listening period of my life this far. And so the layers of a life are sedimented on top of each other, distinct but never fully separate.

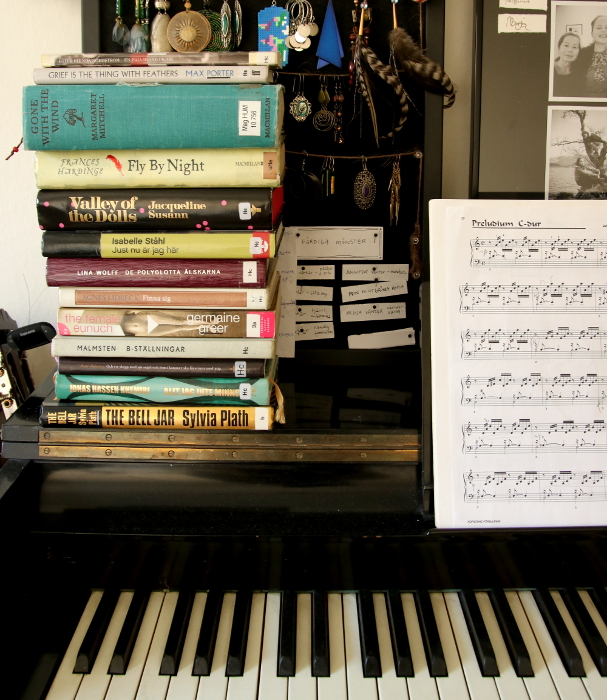

BOOKS

I read 44 books in 2018. And when I look through the list now, I can definitely see a pattern. Many of them have been about the female experience. Feminist literature, in a way. One theme: New Swedish novels by female authors dealing with topics like the sexualized male gaze on the female body (“De polyglotta älskarna” by Lina Wolff), the narrow roles of the girlfriend, the mother and the caretaker that women have to live up to (“Finna sig” by Agnes Lidbeck), and also just being young and generally lost in modern life (“Just nu är jag här” by Isabelle Ståhl).

A second theme: I started a project. I want to read the book “How to be a heroine, or, what I’ve learned from reading too much” by Samantha Ellis. It is a feminist reading of some of the English language classics that many women grow up reading, and what kind of ideals they might foster in a growing person. I love these kinds of books! But being Swedish (and therefore spending most of my teens reading Swedish language classics), there are several of the heroines that are being discussed in “How to be a heroine” that I know of, of course, but haven’t actually read myself. So. I took the reference list of the book and made a little reading list for myself: the literary heroines to get better acquainted with before I pick them apart together with Samantha Ellis. It has been a very exciting and enlightening journey. I have read children’s classics like “Anne of Green Gables”, scandalous romances like “Lace” by Shirley Conran and “Riders” by Jilly Cooper, romantic classics like “A room with a view” and the absolutely fascinating, revolting, captivating melodrama “Gone with the wind”. As well as one of the cornerstone books of second wave feminism: “The Female Eunuch” by Germaine Greer, to give some perspective to all the romance. And I am not done. There are still many books on my list of readings before I can take on “How to be a heroine”. I have no idea if the book itself is even close to being good enough to deserve this kind of preparation – but I am thoroughly enjoying myself, plowing through the stories about classic literary heroines across the whole spectrum of respectability. So it does not really matter.

And a third theme: Women in war. Or, one of the most impressive books I have ever read, Svetlana Alexievich’s “War’s unwomanly face”. Through hundreds of interviews with women who fought for Russia in the second world war, in the words of the women themselves, she tells a heart-breaking story of what it meant to fight for your country, and then be despised for it, looked upon with suspicion, sometimes even forgotten. It shook me somewhere deep, and changed my understanding of the way stories can be told. “War’s unwomanly face” is definitely the best book I read in 2018.

MOVIES

I went to the movies exactly twice in 2018. First, I saw “Phantom Thread”. It was a captivating film, beautiful, a challenging story. A bit weird, though.

Then, I saw the documentary about Ursula K. Le Guin. Now, that was an interesting film. I have liked Le Guin’s books since I was a teenager, but I had no idea she was that interesting as a person. A really nice film, as far as documentaries go.

And then I saw “The Bridges of Madison County”. Better late than never. You know, I like dialogue-driven movies. One of my all time favorites is “Before Sunrise”, which is basically just a two hour uninterrupted conversation. And, in a way, so is “The Bridges of Madison County”. And Meryl Streep is amazing. So, I pick that as the best movie I saw during 2018.

TV SERIES

I watched a lot. Few things stuck, though. I watch a lot of just OK stuff, because they don’t require me to focus too much and I can engage in the main activity instead, that is, my knitting.

But I watched the sitcom “You’re the Worst”. That was entertaining.

PHOTOGRAPH

There are many nice photos that I took during 2018 in the botanic gardens I visited. There were seven in total. I’ve only published one of the posts I wrote about them on the blog, though, so the rest of the garden photos will pop up here eventually. When I have the time.

But it wasn’t one of the garden photos that ended up being the best one. No, as per usual, the best photo is one with people. This one, taken with Hanna and Kirke at the patisserie Miremont in Biarritz during our first afternoon in this lovely (and expensive) town. I feel like there are so many perspectives to this image.

KNITTING

I worked on a couple of bigger projects in 2018, things that I haven’t finished yet. But I made a bunch of mittens. I think I like the swallows I made for my aunt’s partner Jukka the best.

And the Icelandic style sweater I made for David. He wears it all the time.

So, finally, that was my pop cultural 2018.