How we change through life fascinates me. Tastes, for example. Some change happens with active practice, like learning to love smelly cheese or wine. Other change surprises you. Growing up, I never liked marigolds. This orange flower, so common in ornamental flowerbeds, I thought they looked stiff, they smelled disgusting. Were just too orange.

And then I went to Oaxaca to attend the PECS conference. It was a tumultuous time in my life, I had worked myself too hard, the world seemed disjointed, people around me didn’t make sense to my muddled mind, I was exhausted. An absolutely awful travel companion. And so I arrive in the middle of the Día de los Muertos celebrations, to this beautiful old city all covered in marigolds. The traditional Mexican flower of the dead. The smell of them followed me around, spreading from the adorned doorway arches and enormous flower-covered altars placed all over town. Everything orange, purple and laden with bread and painted skulls.

And then the PECS conference started. And it can’t only have been the content of the conference, it must also have been the state I was in. Exhausted, confused, in the very beginning of my PhD, completely open to this beautiful place all covered in marigolds. But. I can see so much of what is now taking shape in my PhD thesis, trace it back to ideas I was inspired to from sessions at the conference, mescal-infused conversations with fellow attendees during mingles and in the evening. It was a defining moment, drenched in the taste of mescal and smell of marigolds. The three years since have been a journey to see how those ideas have unfolded and evolved.

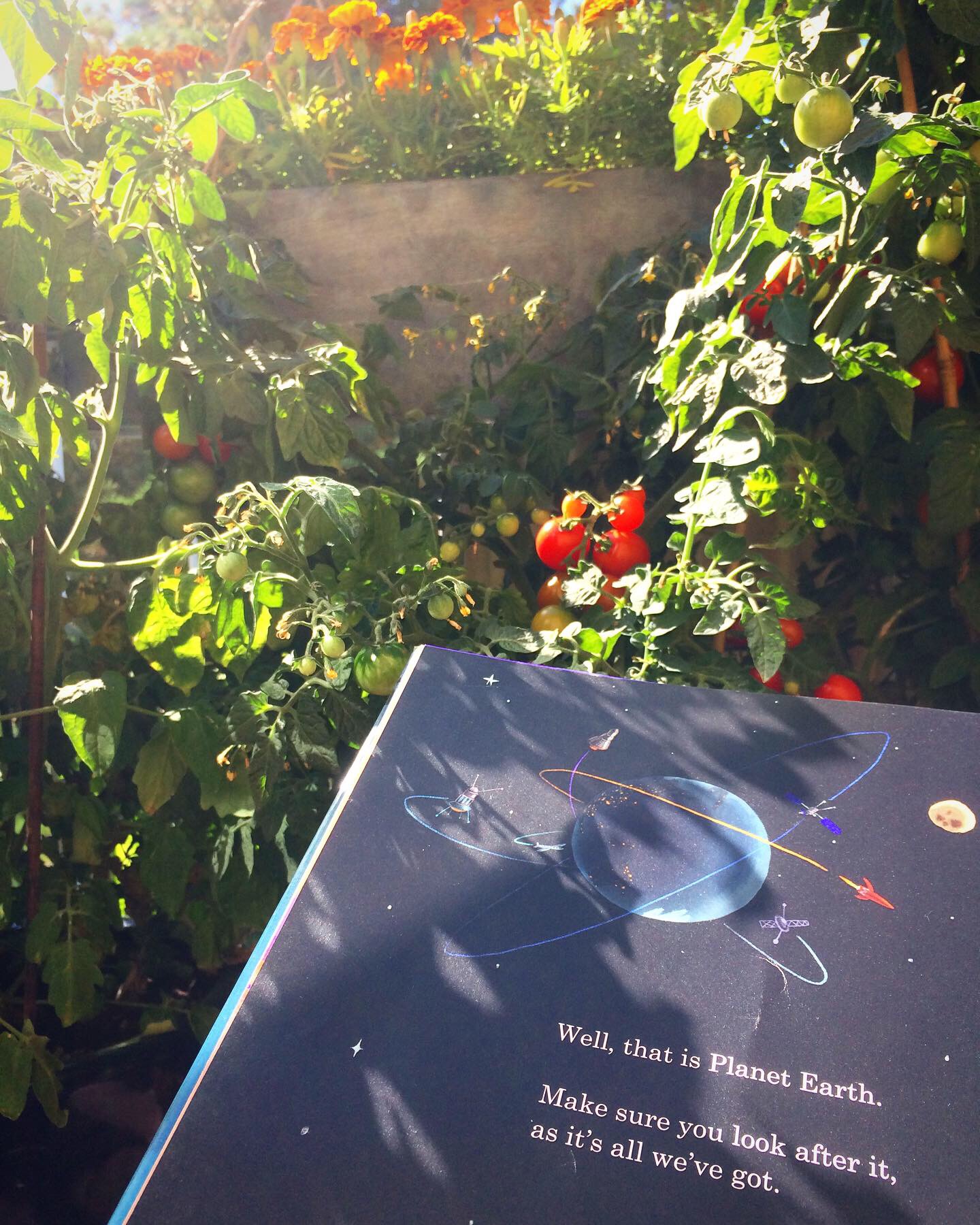

Since then, I love marigolds. I even love the way they smell, sweet, itchy. In March, I planted so many seeds, carefully tended to the growing seedlings in my living room window, next to the aspiring tomato plants and chilis. Now, they live on my lush balcony. They give me a sense of joy, the tableau they create through the open balcony door when I sit in my knitting and reading chair. Especially when it rains. The sound of the heavy summer drops on the roof, the smell of moist soil, the intensity of greens, bright chili leaves, darker tomato, the bluish tint of the pine needles just beyond, and then brighter again, in the ash tree. Purple-gray shades on the clouds. And in the middle, orange, creating a contrast so deliciously seductive, the marigolds. I can’t get enough. And there I am, changed.

Photo: 1. Bed of marigolds in Jardín Ethnobotánico de Oaxaca, Mexico, November 2017, 2. View of my balcony in rain, Stockholm, July 2020. Posted on Instagram August 5, 2020.